“Study hard what interests you the most in the most undisciplined, irreverent and original manner possible.”

– Richard Feynman

One of the most inspiring lessons I learned from attending a meet-and-greet with Steve Vai last year is that everybody has to start somewhere.

During the Q and A session, Steve made it abundantly clear that even though his interest in music came naturally, playing the guitar did not. In his own words, “I had to work my ass off.”

Early on in his journey, he experienced a pivotal moment that forever impacted how he studied and practiced the guitar.

He was taking lessons from a local guitar talent, Joe Satriani, who was a few years his senior. In one of their first classes, Joe gave Steve his homework — memorize all the notes on the guitar. He would be tested in one week.

“Ah, there’s no way,” Steve thought. “I’m never gonna memorize them, because I just can’t.”

In the following lesson, the first thing that Joe said to Steve was, “Play an F# on the B string.” Of course, Steve stammered and fumbled.

“Stop,” Joe told him. “Go home. Don’t come back until you know all the notes.”

Before kicking Steve out, Joe wrote in Steve’s notebook, “If you don’t know your notes, you don’t know shit.”

After Steve walked out the door, he overheard Joe’s mom asking him how the lesson went. “My best student is losing his brain,” Joe replied.

Walking home that day, the words “best student” rang in Steve’s head. He realized that no matter how passionate he was about music, or even how bad of a memory he thought he had, there was absolutely no excuse when it came to learning. “You will never not know your lesson solidly,” he said to himself.

Since that incident, Steve studied copiously and advanced quickly through his lessons. And as he neared the end of his tutelage under Joe after about 5 years, their lessons evolved into 6-hour jams.

As this story demonstrates, learning a new craft can be easily daunting. But with determination, patience, and time, it can be done.

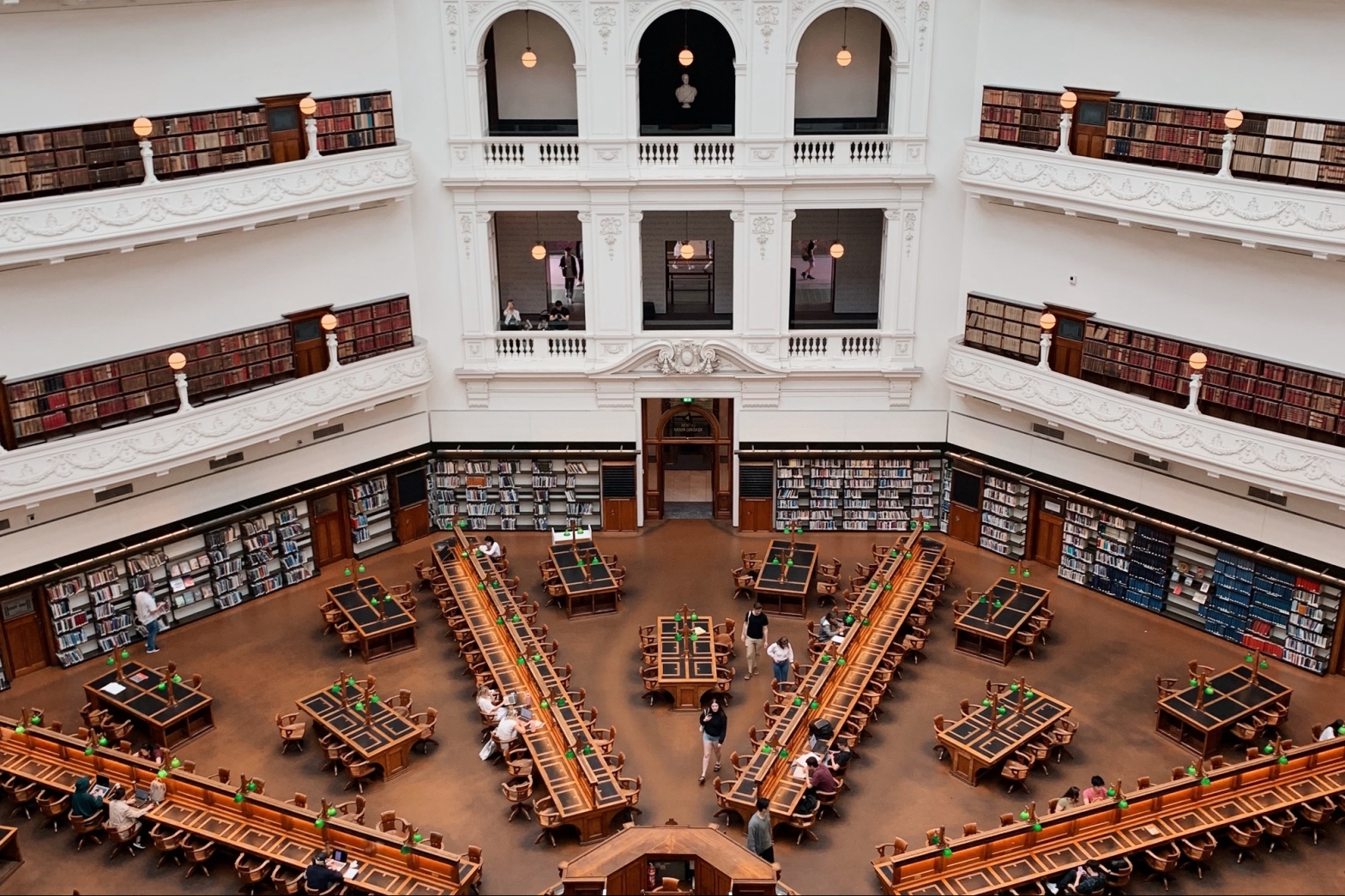

But there’s one important thing that the story doesn’t tell us, and it’s how it can feel especially overwhelming when you look at an entire library of information, thinking that you have to be familiar with every nook and cranny of your craft in order to be good at it.

We ask ourselves, “How do we know which concepts are useful for us to learn? How do we know what to know?”

The story partially answers these questions, in that the basics must be learned. When it comes to learning a musical instrument like the guitar, for example, knowing your notes is fundamental. Because if you don’t know your notes, it would be very difficult to learn just about everything else in music theory.

But what about the other concepts that are not so fundamental?

In their recent interview with Rick Beato, both Steve and Joe gave their practical two cents on this matter.

They were discussing the relevance of music theory, considering all the debate on whether it’s worth learning. After all, many great musicians, including Kurt Cobain, and even Jimi Hendrix, never learned music theory.

Steve and Joe’s advice can be well summed up in terms of learning what you personally think is interesting to you, and also what is necessary for you to authentically express yourself in your art.

As Steve advised, “You need to understand your instrument as deeply as you need to, to get your particular uniquely creative point across.”

Say, for Kurt Cobain, a sparse and rudimentary guitar-playing style was the most natural direction for him to go, in order to say what he wanted to say with his music. It wouldn’t have made sense for him to have an intricate technique such as Steve Vai’s.

Meanwhile, Joe suggested an approach to learning that he has always shared ever since he was a young teacher. He said, “There are no rules. It’s just cause and effect.”

You always have to figure out the context of what you want to say. If you want your audience to feel a certain way, you can try playing a certain note. And if you can’t find the right note, it’s necessary for you to learn more.

He explained, “How do you know which note is the sad note, the kind-of-sad note, the melancholy, the happy-but-a-little-sad, happy-but-not-ecstatic, ecstatic, super happy, out-of-your-mind happy, losing-your-mind happy, I’m-gonna-explode happy? What are those notes? What are those scales? What are those chords? They exist. It’s all in context.”

A practice that he likes to play out with his students is to write music for a scene. He would give a scene, like a baby taking their first steps. He would then switch the scene — suddenly, there’s a kitchen knife, and blood all over the baby. Each scene has its own emotional context, and they each deserve a different set of notes.

With all of this being said, Steve and Joe’s advice shouldn’t be taken as an excuse for you to stay stale, or to limit yourself to a certain style.

Even as you stick to what feels natural to you, there are always new ways that you can learn and experiment with, so that you can articulate a wider range of emotions and thoughts that you experience.

To paraphrase Joe, if you’re a cook, you’re not going to go far if all you know is sweet and savory. Likewise, if you’re a carpenter, it wouldn’t help if all you know is how to use a screwdriver.

Personally, I find Steve and Joe’s advice encouraging, as well as discouraging in a way.

On one hand, it gives us a practical perspective on learning our craft and applying our knowledge.

Yet, on the other hand, it doesn’t necessarily make our work as artists any easier. Because as their advice implies, there are no one-size-fits-all solutions in art.

No one but ourselves can figure out what we’re trying to say, and what kinds of knowledge we need to go about delivering that message through our art.

This is what makes art a lonely business.

I’m reminded of a letter that the novelist John Steinbeck wrote to his former professor, Edith Mirrielees, who taught him creative writing in Stanford University. In it, he described how, even as a seasoned writer, starting a story still “scared him to death.”

Reminiscing his days in class, he wrote, “I was bright-eyed and bushy-brained and prepared to absorb from you the secret formula for writing good short stories, even great short stories.”

“You cancelled this illusion very quickly,” he continued. “The only way to write a good short story, you said, was to write a good short story. Only after it is written can it be taken apart to see how it was done. It is a most difficult form, you told us, and the proof lies in how very few great short stories there are in the world.

“The basic rule you gave us was simple and heartbreaking. A story to be effective had to convey something from writer to reader and the power of its offering was the measure of its excellence. Outside of that, you said, there were no rules. A story could be about anything and could use any means and technique at all — so long as it was effective.” (Emphasis mine.)

He ended his letter by saying, “It has never got easier. You told me it wouldn’t.”

Such is the nature of our work. It never does get any easier.

But we can always keep trying and learning, again and again.