“We never say sorry in our house. We just pretend things didn’t happen.”

Paul McVeigh,

The Good Son

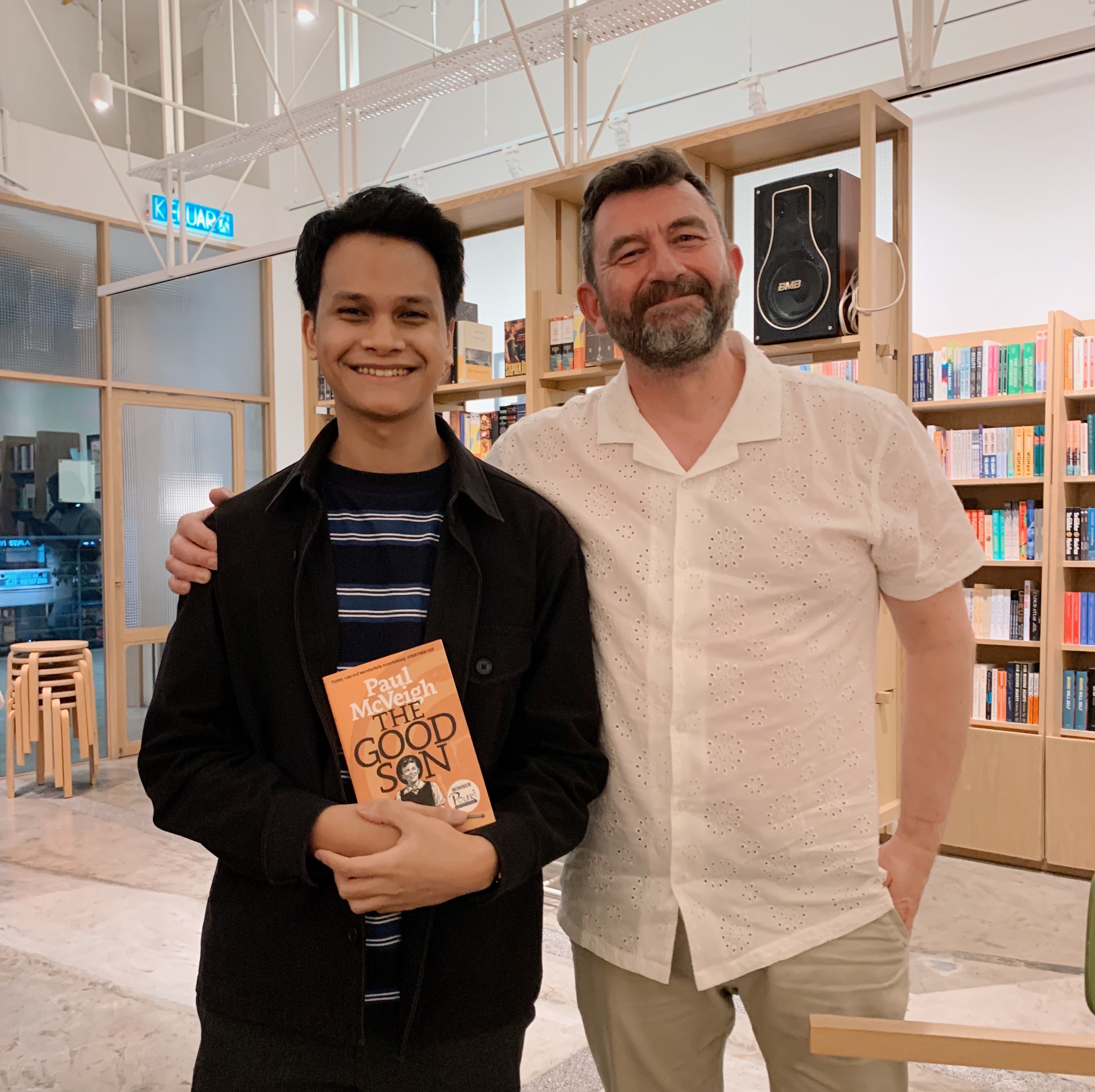

Last week, I attended a talk by Paul McVeigh, who wrote the novel The Good Son — a coming-of-age story narrated by a young boy who learns to come to terms with the cold ways of the world. The novel is inspired by his own childhood, growing up in Northern Ireland during The Troubles — a violent conflict between largely Catholic Ireland and largely Protestant England.

Despite the dark background in which the story takes place, it is actually written as a humorous book. Not only does this come from Paul’s background as a comic, but also because humor plays a big role in how the characters cope with their situation, just as how Paul and his family coped with theirs.

At least to me, the book is more of a coming-of-age story, than being about The Troubles itself. Most of all, it made me think about how out of nostalgia, we tend to romanticize or idealize our past — particularly in the case of this book, our childhood.

During the talk, I got to ask Paul about this aspect of the book.

“Hi Paul,” I said. “So I’ve actually read your book. And it’s a wonderful read.”

“That’s lucky,” he replied, sighing in relief. “Imagine how awkward it would be if you had read the book and said it sucked…Yes, your question is?”

After a round of laughter, I said, “Well, one of the things I loved most about your book is how you gave a realistic take on childhood. We tend to romanticize our childhood as being a much simpler time, when it really isn’t. It came with its own sets of anxieties and insecurities — and not to mention the fact that kids can be really mean to each other. I’m just curious to know, did the process of writing this book force you in any way to look back at your own childhood differently than you used to?”

In response, he told the audience that prior to working on the novel, he never realized how normal all the traumatic events that happened during The Troubles were to him.

It made him realize too, about how abnormal his childhood was, and that perhaps, a “normal” childhood or a “normal” family doesn’t exist.

Despite being fictional in nature, most of the crazy things that happen in the novel either happened in real life to himself, or to other people that he knew. As he explained, “A story doesn’t have to be true, as long as it is emotionally true.”

He really did once wake up with a gun pointed to his face. He really did have to walk over dead bodies to get to the grocery store. He really did see people in his community get tarred and feathered or have their knees shot off.

But to show how normal and everyday these events are to the character, as they were to Paul in his childhood, the events appear in the book merely as short and dispassionate descriptions. It’s as though these events are nothing unusual, and nothing so consequential to the narrator’s story. It’s much like how we tend to regard our own traumas, by just sweeping them under the rug, or locking them someplace far inside our heads.

This brings me to the point I’m trying to make in this article, that is, nostalgia can be distortive. The illusion that the grass is always greener on the other side applies not only to our materialistic wants, but also to our nostalgic wants — or in other words, our desire to recapture our “paradise lost”, or a past part of ourselves that we can never truly regain.

It’s only in our human nature to long for things that we don’t or no longer have. Such things always look better and more enticing, even if they aren’t in actuality. Through our rose-tinted glasses, we see only our object of desire in all its beauty, while we conveniently ignore the uglier and boring aspects. Particularly when it comes to our nostalgic desires, we crave the false comfort of the familiar, even if the familiar was harsher than we would like to remember.

Perhaps the earliest recorded story we have of this human condition is that of Prophet Musa (pbuh), or Moses, and his people. In Egypt, their lives had been a nightmare, as they suffered under the brutal regime of their Pharaoh. They were finally saved when the Pharaoh drowned in the Red Sea. Musa then led his people to the Promised Land, or Palestine, where God promised them prosperity.

But the journey was far from easy. They trudged through scorching and lonesome deserts, far from any trace of vegetation and civilization. As they suffered their present hardship, they suddenly became nostalgic for their past life in Egypt. So what that they were regularly tortured and abused, they thought. At least it was a familiar environment to them.

Even after God eased their journey and sent down the best food that they could ever get, which was manna and salwa from Heaven, Musa’s people only benchmarked them unfavorably with the melons, cucumbers and meats that they had back in Egypt.

Recently, I found myself fantasizing about changing jobs, mostly because I was frustrated with certain people that were difficult to deal with. So I toyed with the idea of working at a company I used to intern in. I even longed for “simpler times” as an undergrad, when it was seemingly just about classes and chilling out.

But then I realized, no matter where I go, there will always be difficult people that I have to deal with. I remembered how it was during my internship. There were many times when I was so emotionally drained. Part of my job was to handle customer relations, and that meant managing the company’s social media accounts. And you know how unfiltered people can be on the Internet. With every mean and uncalled-for message and comment I got, all I could do was send a friendly reply — despite me feeling like I just wanted to strangle the lights out of those people.

Likewise, being an undergrad wasn’t all that fun either. Among other things, there were the headaches from doing group assignments, particularly in dealing with free-riders or other members’ half-assed efforts.

Don’t get me wrong, though. Of course, in certain situations it may be a good decision to follow where your nostalgia leads you. But you have to be honest with yourself on whether that decision will truly be fulfilling and reasonably healthy for you. For example, if you’re considering going back to a job that was abusive in any way, that is already a big red-flag.

Think back on your past. Maybe it is your childhood, or a relationship, or a job that you previously had, that perhaps isn’t actually as great as you’d like to remember. Were there any aspects of it that were abusive or toxic, that you previously accepted as normal?

It’s worth thinking about it from the other side of the coin, too. What sort of behaviors did you do that were unreasonable or immature? How much have you truly grown since then?

Remember that nostalgia can be beautiful, but it can also be seductively distortive. Whenever you’re making an important decision, always consider if the nostalgia factor is weighing on your judgment.

More often than not in life, it may not be about wanting and getting (what we imagine are) better things, but simply making the most out of our present lot.

Leave a comment