Prelude

“It’s nice to be known as a legend, and people will pay to see one, but for most people, once is enough.”

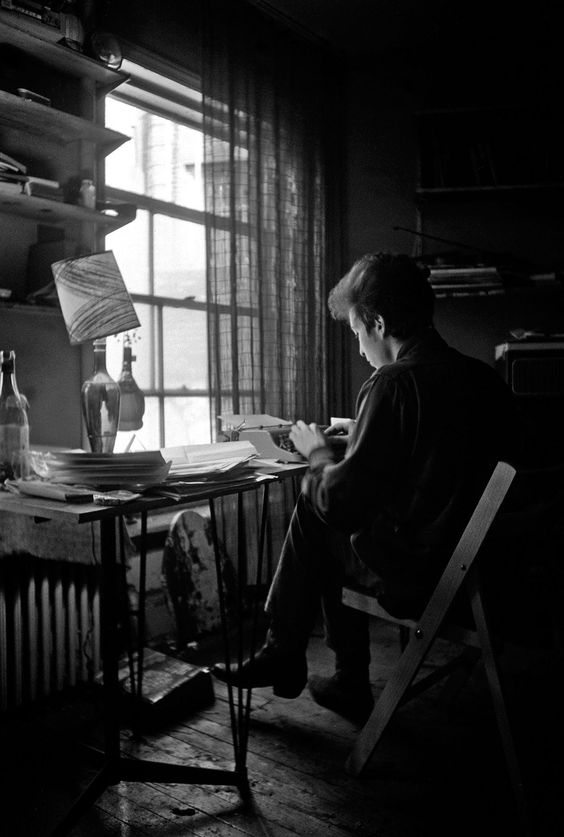

The phone had been ringing for two weeks, it was the Nobel committee. They had recently announced that he was the winner of the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature. Bob Dylan ignored the calls as he sat and scratched his head, taking all the time in the world to reflect on how he had never thought of his songs as literature. Though he didn’t attend the ceremony to give a speech, he eventually went to receive his medal on a tour stop in Stockholm, Sweden — Looking more like a cat burglar than a Nobel laureate — Wearing dark clothes and a hoodie, being handed the medal through a door. He didn’t like the attention.

Bob Dylan is one of the greatest living songwriters that the world has to offer, one worthy to be called a poet. Some critics have even gone further, naming him “the Shakespeare of our time”. His songs are our arsenal in understanding the human condition. He had used many creative devices in his songwriting to either make us feel alright, or to punch us in the face, just as his hero Woody Guthrie said, “It’s a folk singer’s job to comfort the disturbed and to disturb the comfortable.”

His iconic folk songs in the early days were even instrumental in advancing the Civil Rights Movement — Dylan performed in front of hundreds of thousands of people in the March on Washington — The same event in which the great Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have A Dream” speech.

But to simply say that Bob Dylan is a towering figure in folk music would be an understatement. He is just as much of a giant influence in rock music.

To list his greatest songs would be like fitting the history of the entire world in one textbook, from the time when he was a folksinger, belting out world-changing lyrics such as “Blowin’ In The Wind” and “The Times They Are A-Changin’ ” to when he transitioned into a rockstar, snarling out songs such “Like a Rolling Stone” and crafting his poetic songs such as his surrealist tour de force, “Desolation Row”.

But it’s fair to say that when Dylan is praised for his genius, we’re referring to his early work. His first album, Bob Dylan (1962) was mostly made up of cover songs. Beginning with his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963), he then wrote a string of masterpieces, ending with Blonde on Blonde (1966). Then, after a slew of divisive albums, he wrote Blood on the Tracks (1975). It was his last great album.

He had always been a bit of a mystery, hiding behind this Bob Dylan persona he created, all to mislead journalists and writers. Only in recent years had he opened himself up with candor about what his songs meant and what really went on in his life.

Though Dylan went on to write a large body of new material, they could never amount to his early work. They feel rather dry and mild, as if he is tired of being the Bob Dylan that we so needed — A singer who had things to say — Things that no one else had the guts to articulate.

In the following parts of the article we will learn about Dylan’s story, and the lessons we can obtain so that we could emulate what worked for his success, and take heed of what caused his unfortunate creative downfall.

Rise

“My father, who was plain speaking and straight talking had said, ‘Isn’t an artist a fellow who paints?’ when asked by one of my teachers that his son had the nature of an artist.”

Dive Deep Into What You Love

“Sometimes that’s all it takes, the kind of recognition that comes when you’re doing the thing for the thing’s sake and you’re on to something — it’s just that nobody recognizes it yet.”

Dylan grew up in an average, unassuming Minnesota family. Though it was hard enough for him to get decent grades in school, he had an insatiable hunger for the things that he had profound interest in, particularly music. He was like a sponge, always learning from other people, easily picking up their styles, their accents, and their mannerisms.

His life changed when he first listened to folksinger Woody Guthrie. “It was like I had been in the dark and someone had turned on the main switch of a lightning conductor,” he said.

Folk songs were no ordinary music for Dylan. “You could listen to (Woody Guthrie’s) songs and learn about life,” he once said. They were much more important than light entertainment. Folk songs were sung with clarion, urgent things to say, that if we understood them, they would help change us for the better. For Dylan, they were his way of exploring the universe.

He didn’t have any folk records so he would hang around in a friend’s house who had so many of them, and he would listen to them for hours in a day.

“One by one, I began singing them all, felt connected to these songs on every level,” he said, “One thing for sure, Woody Guthrie had never seen nor heard of me, but it felt like he was saying ‘I’ll be going away, but I’m leaving this job in your hands. I know I can count on you.’ ”

Little was known of Woody Guthrie at the time, if he was still alive and well. Dylan learned his songs and played them as if all the poetic words were his own, trying to find out who Woody Guthrie was. There was a lot more to learn than just songs and picking styles. He wanted to capture the essence.

He said to himself that he was going to be Guthrie’s greatest disciple, and that he “decided then and there to sing nothing but Guthrie songs. It’s almost like I didn’t have any choice.”

This indelible work ethic of his was not only applied to learning folk music, but also in feeding on other interests. He crammed his brain with long poems from his favorite poets, especially Arthur Rimbaud and T.S. Eliot, and challenged himself if he could remember the verses he had read.

He also fed his mind and built his knowledge of human nature from many novels by great writers such as William Faulkner, John Steinbeck, Remarque, and even works of non-fiction by writers such as Machiavelli, debating on whether his ideas made sense to him.

Some people are afraid to tailor themselves to an artist whom they admire — It makes them feel like an impostor — That they don’t have their own voice. But it’s an essential part in the road to mastery. It’s okay to pattern yourself after another person. You’re in the learning process. Even the Beatles were a cover band for years before they started writing their own songs, the reason being “to avoid other bands being able to play our set”.

Build Your Vocabulary

“I can’t say when it occurred to me to write my own songs…I guess it happens to you by degrees. You just don’t wake up one day and decide that you need to write songs, especially if you’re a singer who has plenty of them and you’re learning more every day.”

For nearly four years, he learned how to write songs from analyzing folk lyrics. All he listened to and all he played were folk standards.

As time went on, Dylan felt as if he was hitting a learning plateau in assimilating Woody Guthrie songs, although he didn’t want to. He slowly developed his voice in the process. The first song he ever wrote was “Song to Woody”, in which he expressed his utmost gratitude to his hero.

Dylan once said in an interview that songwriting is an age-old process. Its evolution is like a snake with its tail in its mouth — It’s a cycle that has always been the same and will always be the same. There’s nothing really new under the Sun.

Laywers change old laws to fit the current generation, and old songs give us ideas to build new songs on.

Folk songs were everything to him. “Trouble was,” he said, “there wasn’t enough of it. It was out of date, had no proper connection to the actualities, the trends of the time. It was a huge story but hard to come across.”

When he was learning to write his own songs, Dylan would reverse-engineer his favorite songs and poems — Taking them apart to see what lies behind the misty curtain — Discovering what made them so effective.

In practice, he would take an existing melody and write several songs off it. Or he would take some old lyrics and change them, adding his own voice to them. Not that he would sing any of them onstage.

When he wrote his songs, he would muster his knowledge of songwriting that he derived from the musicians he listened to in a myriad of creative ways.

If one takes the effort to examine Dylan’s roots, one can see how they influenced him in creating new compositions. In the song North Country Blues, for example, you would notice that there is a narration of tragedy in every verse — A songwriting device that he had learned from Woody Guthrie.

Also, revealing how he came to write some of his most legendary songs, Dylan explained, “If you sang ‘John Henry” as many times as me – ‘John Henry was a steel-driving man / Died with a hammer in his hand / John Henry said a man ain’t nothin’ but a man / Before I let that steam drill drive me down / I’ll die with that hammer in my hand.’ If you had sung that song as many times as I did, you’d have written ‘How many roads must a man walk down?’ too.” (That song is “Blowin’ In The Wind”)

As researched by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in his book Creativity, it’s commonplace to hear about how the world’s greatest creatives dedicated themselves to deliberately studying or even memorizing the works of other figures whom they admire, before they ventured on to create their own.

Take filmmaking — Francis Ford Coppola had the play “A Streetcar Named Desire” that he read over and over again when he was little. Stanley Kubrick on the other hand watched Coppola’s The Godfather at least ten times.

There are plenty of other examples, they aren’t hard to find.

It takes a long time before you can create something really authentic, of your own voice, something great — At least longer than you think.

Tim Ferriss adviced that you should make the commitment to give yourself at the very least, three years to learn your craft and become good at it — To study, to try creating, failing, failing again, and failing better.

Consider how long it took for the author Ryan Holiday. He dropped out of college at age 19 to learn the craft of writing from Robert Greene. He didn’t publish his first book until he was 27.

Fuse The Contemporary With The Timeless

“In another millions of days, thousands of millions of days, what would it all mean? What does anything ever mean? I try to use my material in the most effective way.”

It was a time when people were insensitive towards freedom, hence the rise of prominent leaders such as Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr, who stood valiantly in the fight against injustice. The young turks, the college student age people like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez were put into positions of leadership — Their weapon of choice wasn’t rah-rah speeches, but folk music.

Professor Sean Wilentz wrote of Bob Dylan, “Dylan’s genius rests not simply on his knowledge of all of these eras and their sounds and images but also on his ability to write and sing in more than one era at once…To make the present and the past feel like each other.”

What made Dylan’s songs so great was that they were aimed at mostly social issues of that time — The raging of the Civil Rights Movement, the assassination of President Kennedy, the nation at war — But at the same time, they had lasting flavors that stand the test of time — Themes such as racism, poverty, discrimination — Things that humanity needs to constantly be reminded of, as all that has come before in history will come again in the future.

He articulated what most people wanted to say, but couldn’t say. Sure, he angered some people, but the last thing on his mind was to please everyone. His job was to say what he felt needed to be said, as long as he was being honest.

At the pinnacle of his success in folk music, he was presented the Tom Paine Award, just weeks after President Kennedy was assassinated. Everyone expected a heroic speech from Dylan, but that’s not what they got.

“I got to admit that the man who shot President Kennedy, Lee Oswald, I don’t know exactly where — what he thought he was doing, but I got to admit honestly that I too — I saw some of myself in him,” he said.

Shortly afterwards he was forced to issue a statement making it clear that he didn’t identify with Oswald.

Follow Your Intuition

“An artist has got to be careful never really to arrive at a place where he thinks he’s ‘at somewhere’. You always have to realize that you’re constantly in the state of becoming. And as long as you can stay in that realm, you’ll be alright.”

For many artists, a time will come when his craft calls him to progress, to explore new places — He’ll come to a crossroads where he’s given an ultimatum — The opportunity for growth, or his present comfort and stability.

For Dylan, walking away from the folk scene was a very bold move. He had to alienate many of his folk fans to go where his art was calling him.

Slowly moving towards a new endeavor of songwriting in the album Another Side of Bob Dylan (1964) where “there aren’t any finger-pointin’ songs”, he kept learning and experimenting — Moving on with electric instruments in Bringing It All Back Home (1965) — And perfecting the great, highly influential rock sound in Highway 61 Revisited (1965).

Quitting on being the people’s singer, and sick of the fame, he wrote his 6-minute bonafide classic, Like A Rolling Stone. He said, “It suddenly came to me that that was what I should do. After writing that, I wasn’t interested in writing a novel or a play or anything. Like I knew I just had too much. I just wanted to write songs.”

The only acoustic song in Highway 61 Revisited was the closing track, “Desolation Row” — A series of vignettes that weaves characters from history, fiction, and religion in an alternate world of chaos and dystopia. It’s often praised as Dylan’s own masterful counterpart to T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land”.

His intuitive feel for musical creativity made him a very challenging musician to work with. In the studio, not fully knowing what the songs were like was an entirely normal thing.

Bob Johnston, a producer who worked with him on several albums reflected, “He never did anything twice. And if he did it twice, you probably didn’t get it.”

He would transition from one song to another as if they were part of a medley. Sometimes he would have several bars, or he would change his mind about how many bars there should be, or he would eliminate a verse, or add a chorus when others didn’t expect it. He’d have his band play in different keys and different speeds, and interrupting them often, saying “That’s not the sound. That’s not it.”

If he was asked, “How are we going to know when the song will end?”, he would simply respond, “Oh, when we know it’s done, it’s done”. As a result, not only were the songs played for their lives, they were coupled by the joy of discovery.

If that’s how he worked in the studio, you can probably guess what it’s like to play in his live shows — For him, his songs aren’t written in stone, hence he constantly reinterprets the lyrics, starts them off and plays them to the end in very different ways than on the record. Just for the song “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” alone, God knows how many different sets of verses that he’s made up on the spot by now.

Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers are a few of the people who not only survived, but grew through the challenge. Petty said, “It’s a very spontaneous kind of music. Arrangements can change very quickly. Maybe a song comes up that you never rehearsed before, and you just do it.”

Mike Campbell, the guitarist for the Heartbreakers said, “They were some of the most crazy, enjoyable times I’ve ever had playing live because it was such anarchy. One of the things that we learned from him is that by breaking all that down, these accidental things would happen, which is magical — It would never happen if you just played your shows stocked from start to finish. And that was what he was reaching for — Those bigger moments, these places where new things happen, where spontaneous things happen.”

Fall

“Sometime in the past I had written and performed songs that were most original and most influential, and I didn’t know if I ever would again and I didn’t care.”

After Highway 61 Revisited came another great album, Blonde on Blonde, which featured some of his most imaginative compositions, such as Visions of Johanna.

Post-Blonde on Blonde, Dylan wrote some decent albums, even the soundtrack for a movie in which he had a role (He later regretted it). Then came a tumultuous period in his marriage, which marshaled him to write the album Blood on the Tracks — An album that cemented his name as the great American poet.

Returning to a more sentimental, acoustic sound, it was his blood on those tracks, alright. His son, Jakob Dylan said that those tracks “were my parents talking”.

But for Dylan, his well of creativity was drying up from exhaustion. He felt uninspired, tired, and that he was losing his hunger — But he kept going anyway. After Blood on the Tracks, his later compositions didn’t have the same electricity as his older work.

He also wanted to live a more private life, where he could just be a father and send his kids to school and become an active participant in his family’s lives — A life in which no one would turn their necks and stare at him in restaurants, whispering to one another, “Is that really him?” — A life that he didn’t get. Everyone wanted a piece of him.

He confided in his memoir, “I had a wife and children whom I loved more than anything else in the world. I was trying to provide for them, keep out of trouble, but the big bugs in the press kept promoting me as the mouthpiece, spokesman, or even conscience of a generation. That was funny. All I’d ever done was sing songs that were dead straight and expressed powerful new realities. I had very little in common with and knew even less about a generation that I was supposed to be the voice of.”

With his heart not being at ease, he was losing his essential ingredients for creativity. “It’s hard to live like this. It takes all your effort. The first thing that has to go is any form of artistic self-expression that’s dear to you. Art is unimportant next to life,” he said, “And you have no choice. I had no hunger for it anymore, anyway. Creativity has much to do with experience, observation and imagination, and if any of those key elements is missing, it doesn’t work. It was impossible now for me to observe anything without being observed.”

During his long tour with Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers in the mid-1980s, the burnout was revealing itself in ways that he just couldn’t ignore any longer.

While Petty and his bandmates were having the time of their lives playing for their hero, Dylan was silently trudging through turmoil.

“The public had been fed a steady diet of my complete recordings on disc for years,” he said, “But my life performances never seemed to capture the inner spirit of the songs — had failed to put the spin on them. The intimacy, among a lot of other things, was gone. For the listeners, it must have been like going through deserted orchards and dead grass.”

He felt that everything had become monotonous, that “My performances were an act, and the rituals were boring me. Even at the Petty shows I’d see the people in the crowd and they’d look like cutouts from a shooting gallery, there was no connection to them — just subjects at random. I was sick of it — sick of living in a mirage.”

Most heart-wrenching was how he’d lost the connection to his own songs. He said, “My own songs had become strangers to me, I didn’t have the skill to touch their raw nerves, couldn’t penetrate the surfaces. It wasn’t my moment of history anymore. There was a hollow singing in my heart and I couldn’t wait to retire and fold the tent. One more big payday with Petty and that would be it for me.”

Unlike other musicians such as Tom Petty and John Frusciante who took retreats often and had never had a “dark era” in their career — Dylan hardly ever took breaks. He worked continuously, moving quickly to the next album. But everyone has their breaking point.

Creativity and inspiration come from our subconscious mind — Yep, true — But it doesn’t just happen. Our subconscious mind is like a well, and we draw our ideas from it. But in order for us to do that, there must be water in it in the first place.

Every artist needs to take the time to not do anything for a while, to go back to square one and start all over again, to learn new things with a beginner’s mind. Think of Frusciante, who always surprised us in every Red Hot Chili Peppers album — Because that’s what he did. He constantly gave himself personal assignments — Studying the works of other musicians that he admired. Only after that, new ideas would float to the surface of his mind.

You can’t just think about the “Aha!” moments without first acknowledging the long hours of intense study that came beforehand.

By now, Dylan has reached the phase of his life where he’s more focused on helping the future generation succeed, rather than on his own success. He’s more convivial and open-minded about doing interviews and accepting awards, debunking the mysteries of his creativity.

Reflecting on songs he wrote in his glory days, he said, “They just came through me, it wasn’t like I was having to compose them. That doesn’t happen anymore, I just can’t write them that way anymore…But I can still sing them.”

Sounds like you know little to nothing of Dylan’s work, post 1966…not that he needs me to defend him. Fair to say his REPUTATION was made in the ‘60s, particularly the misimpression that he was a protest singer of some kind, but to dismiss all that came after? Ludicrous to me.

LikeLike

Ok, let’s do a little experiment and imagine that Bob Dylam never recorded the albums that Mr. Zailan labeled as the greatest. Without those albums, of course he wouldn’t be Bob Dylan, but let’s try to see who he would be. I will choose, in my opinion, the ten best albums from the remaining catalog.

Time out of mind

John Wesley Harding Desire

Basement tapes

Love and the Teft

Modern times

Oh Mercy

Nashville skyline

Rough and Rowdy Ways

Slow train coming

So it seems to me that we could say that he is a great musician. But let’s remember that many of Bob Dylan’s great songs were never released on official albums. Now let’s try to put together a Greatest hits album of songs from albums that Mr. Zailan did not include in the list and those that were not released.

Paths of victory

I shall be realized

Positively 4th street

All along the watchtower

Farewell Angelina

When I paint my master peace

Knocking of heaven’s door

Forever young

Hurricane

Blind Willie McTell

I and I

Every grain of sand

Most of the time

Man in the long black coat

Series of dreams

Things have changed

Girl from the red river shore Mississippi

Not dark yet

Kay West

I could choose 20 others. So, I think that any author with 20 songs like this would be among the greatest.

LikeLike

Thanks for the article.

I agree with Andrew. The work Dylan has done in the last 20 years is a treasure-house all in itself (for the most part). Dry and mild it is not. And I would say that Rough and Rowdy Ways is his last (i.e. latest) great album!

LikeLike

What a strange, strange article. Would you like to print my feature on War and Peace? (Note: I think it’s about Russia.)

LikeLike

Time out of mind, Love and theft, Modern times, Rough and rowdy ways. Has the author of this article heard these albums? Dylans genius continues to inspire as much or more than in the 60s.

LikeLike

I have to say, I mostly agree with the other comments. I think Mr. Zailan does well with his precis on Dylan’s rise, but to ignore everything after Blood on the Tracks is to hit a wall and crash the car. It’s a little like the folks who lost their taste for Dylan after he “went electric.” Now, I do have problems with much of what comes after Modern Times – I think the lyrics are too much a pastiche, and the songs lack cohesion (and I don’t think much of the highly vaunted Tempest or Rough & Rowdy Ways as whole works, though they both contain good songs.) But, to write Dylan off mid-career seems like unfinished research and a rush to completion.

LikeLike

Nice post. I learn something totally new and challenging on sites I stumbleupon every day. It’s always helpful to read content from other authors and practice a little something from their web sites.

LikeLike

Dylan’s own stuff was and will ever be, so much better than Frank Sinatra’s, I cannot help but think that to make three straight lps of Sinatra’s songs was a good signal Bob has been really, really running out of fresh ideas recently. His “human jukebox” set lists have become boringly predictable, and his voice- which was always better known & loved for its message, rather than its timbre- has gone over the falls. Yes his early work is genius. No poets ever say anything worthwhile & eternal after age 30, pretty much anyway, do they…

LikeLike